Making a battle tank with better armor at a third of the weight—the very promise offered by an advanced material called composite metal foam (CMF)—would seem so implausible as to be near-comical. Yet protecting soldiers is deadly serious business. And it’s what spurred steel-CMF’s lead researcher to pursue its development.

“Ever since the Iraq war started and I saw soldiers hurt in the war zone, I felt like my material can help these people,” chief scientist and North Carolina State University (NCSU) professor Afsaneh Rabiei, Ph.D., told an Atlanta television reporter.

Rabiei’s team at NCSU has been collaborating with the US Army’s Aviation Applied Technology Directorate (AATD) to develop composite metal foam, an innovation that could have broad implications for the development of future fighting vehicles.

Built to Serve—and Protect

Each M1 Abrams battle tank, the workhorse of the US Army’s tank fleet, weighs in at a not-so-svelte 60-plus tons. A good chunk of that weight is attributable to the rolled homogeneous armor (RHA) steel plating that surrounds its frame—and protects the tank’s occupants. It only stands to reason that any solution seeking to replace RHA should provide equal or better safeguarding capacity.

And that’s precisely where composite metal foam stands tall.

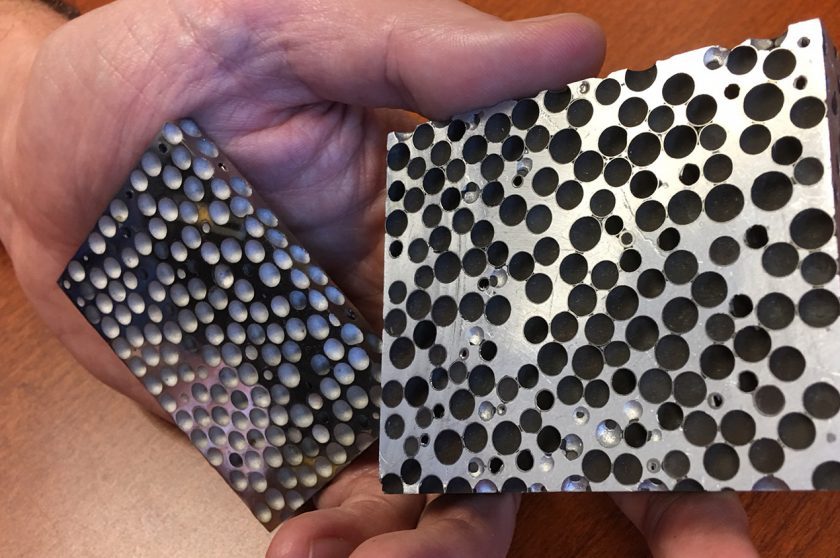

In her early CMF research, Rabiei sought to improve metal foam, which is basically metal that has gas blown into it. A cross-section of metal foam reveals something that resembles a “steel sponge,” with its gleaming surface dotted with a myriad of hollow spheres. It’s that unique structure—and its composite of metal foam mixed with stainless steel—that makes steel-CMF shine.

“It works like heavy-duty bubble wrap,” Rabiei explained to Army Times. “The bubbles inside can squeeze down and provide protection.”

When a projectile strikes steel-CMF, the energy deforms the hollow spheres inside and the metal absorbs the blast. That’s a better result than today’s traditional armor systems, which rely on advanced ceramics bonded to soft “catcher” materials: While the ceramics also can soak up the energy from a bullet or blast, they work just once. steel-CMF provides an attractive alternative to the “one-and-done” model, since it can successfully absorb multiple hits.

To put its steel-CMF prototypes to the test, Rabiei’s team fired a 23×152 millimeter (mm) explosive round—a kind often used in anti-aircraft weapons—at an aluminum strikeplate just 18 inches in front of their 10-inch by 10-inch steel-CMF plate. The CMF took the blow, holding up against not only the blast pressure, but also to the fragments of copper and steel from the round and from the aluminum strikeplate.

In addition to seeing how steel-CMF holds up against hand-held assault weapons and radiation, researchers also turned up the heat on it. What they discovered pointed to another highly practical and valuable benefit of steel-CMF’s special Swiss cheese-like structure: It took heat twice as long to pass through steel-CMF as it did a similar chunk of stainless steel. That heat resistance would give soldiers more time to escape the spread of potential heat-sparked explosions of ammunition stored on the tank.

A Lot Less Running on Empty

When you consider that an M1 Abrams has a fuel economy rating of just .6 miles per gallon, it’s easy to see why trimming every ounce of weight off of it becomes that much more attractive to military planners and logistics officers.

So just imagine the smiles you’d get if you could shave off nine tons.

That’s the promise that steel-CMF could hold, by reducing an average armor weight of 12 tons to just four. The less a tank weighs, the less powerful—and fuel-guzzling—an engine would be required to propel it. Or, if it kept its original powerplant, the tank could carry three times more weight in personnel or ammunition.

Putting Composite Metal Foam in the Field

Given its unique qualities, as it becomes a material that can be mass produced, steel-CMF could prove beneficial to a broad range of applications where “impact” and “weight” need to strike a favorable balance, as they do in car bumpers, bulletproof vests and artificial knees.

For now, though, steel-CMF research continues in military applications, with the Army’s AATD team seeing more near-term applications of the current lab material in ground vehicles like Humvees. Regardless of where they go to work first on the battlefield, Rabiei will be watching with special interest.

“When I received research funding, I was very eager to explore the application of composite metal foams for armor,” she told Army Times. “If I see one person walk out of a deadly situation because of my material, I think I have left my mark.”

The Innovation, Inspiration & Ideas blog was created to share stories and profiles of companies, products and individuals creating innovation in business through inventive material solutions. For more information on why we launched it, read our blog introduction.

Also in University Research:

Bees Provide Solution to Adhesive Failure

in University ResearchAdhesive can present a problem in high-humidity or low-humidity climates, but Georgia Tech researchers may have found a sticky solution by looking at honey bees. Bees collect pollen and carry… Read More

Stained Glass Technique Used to Create Bioactive Glass That Fights Bacteria

in University ResearchLeveraging a technique for making stained glass that dates back hundreds of years, a group of researchers at Aston University (Birmingham, UK) have developed a wholly modern weapon in the… Read More